The Great Migration is the joint longest mammal migration on Earth.

Contrary to popular belief, the wildebeest migration has a competitor for duration. The length of the migration is also mirrored by the lesser known zebra migration in Botswana which sees the striped horses of Africa migrate from the floodplains of Chobe to Nxai Pan. And back again. Both migrations have a journey length of roughly 500km which is no short distance.

It is not just wildebeest that migrate in the Serengeti. The Great Migration contains over 2 million animals, including 300,000 zebras and a whole assortment of antelope such as impala, eland and Thompson’s gazelles. The migration sees the animals move in a general clockwise direction through the Serengeti National Park, following the rains.

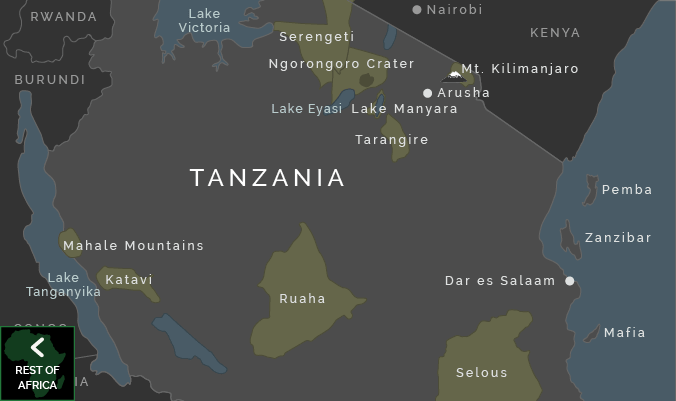

The migration is ALWAYS in Tanzania. No matter what time of year it is, the migration remains in Tanzania all year long. Parts of the migratory herds do move into the Masai Mara in Kenya from July until October; however the large majority of the herds at this time are still in the Northern part of the Serengeti.

The famous river crossing that provides ‘documentary worthy’ footage is across the Mara River. The misconception is that this river crossing is from Tanzania into Kenya or vice versa. In fact the crossings that take place are in both the Serengeti and The Masai Mara, however if the wildebeests are crossing, they will finish in the same country they started. There is also a smaller river crossing across the Grumeti River in the Western corridor of the Serengeti. This is nowhere near as spectacular in terms of size and scale; yet drama including huge crocodiles is still very apparent.

A symbiotic relationship exists between the zebras and wildebeest of the Serengeti. Put simply, without the zebras, the wildebeest wouldn’t be able to survive. Wildebeest are fussy eaters, they are selective grazers and only feed upon the shorter parts of the grass, but luckily for them, zebras are bulk grazers meaning they aren’t nearly as picky over their grass choice. As the zebras graze they essentially act as a lawnmower, cropping the grass and making it palatable for the wildebeest to consume.

Crocodiles can wait a year for their meal. The crocodiles of the Mara River are known to be some of the biggest Nile Crocodiles in Africa and you would expect them to eat regularly. Without going into too much scientific detail, crocodiles can control their metabolism and their heart rate to essentially “shut down” whilst the migratory herds are not in the area meaning they don’t have to feed too often. They go into a state of near-hibernation and their biological system is so sophisticated that it means that the biggest of the bunch may only need to feed once or twice a year.

There is only one type of wildebeest in the Serengeti. The wildebeest in Tanzania are the blue wildebeest. They are referred to as blue because in the sunshine, their glossy coats glisten a shade of blue. The wildebeest may also be named “gnu” by people. This is an interchangeable name and is an onomatopoeic derision of the sound they make. The Serengeti is only home to Blue wildebeest (the brindled gnu) but South Africa is home to another type, the black wildebeest, also known as the white tailed gnu. This type of wildebeest has heavier set horns and is slightly smaller. If you were to visit a breeding farm in South Africa you may even be lucky enough to see a golden wildebeest. A very rare specimen.

The herd isn’t always together. Although the migration is referred to as the mass movement of thousands of animals, the herds don’t all stick together all the time. When there is an abundance of food, the wildebeest can break off into splinter herds and go in search of their own food. The wildebeest also don’t cross the Mara River all at once. You get herds of varying sizes crossing the rivers all at different times from July until October. Even though the movements of herds are the same, it is unlikely that all the wildebeest will be congregated in one particular spot at the same time. There is one time though…

The only time that you will see almost every wildebeest of the migration together is in the months of January and February. This time of year is the calving season and where half a million wildebeest are born in the South Eastern corner of the Serengeti and North Western area of the Ngorongoro Crater. Over a few weeks thousands of new bleating calves enter the world, but this is also a prime opportunity for predators who also thrive at this time of year. The calves that are born are precocial meaning they can stand and are not entirely reliant on their parents within minutes, a vital survival technique that helps them keep up with the herd.

The herds are always monitored and you can check online where the migration is. Guides and pilots send in their information as they see it, about the herd’s locations and movement directions which are then transferred to a website So, if you’re raring to go on a trip or you’re longing to be back after your holiday with us, you can find out what is happening wherever you are in the world!