It is hard to imagine a more appropriate name for this famous national park than ‘Serengeti’, from the Maasai word meaning ‘endless plains’. Although the Serengeti National Park is the most famous and well-visited of all the Tanzania national parks, it remains a land of surprises and unexpected discoveries.

Russet and green grasses and trees spread like a sea beyond each distant horizon. Its vast expanses often appear to be havens of peace and quiet from a distance, and then reveal themselves to be alive with wild, expectant or predatory energy when scrutinised at all.

The Serengeti National Park is one of the most celebrated wildlife reserves in the world. Some credit for such wide acclaim must go to the Kenyans for so diligently promoting their own tiny corner of it. But the recognition it receives from nearly every wildlife filmmaker, the Frankfurt Zoological Society, tourists and the Tanzanians themselves have ensured a conscientious approach to preserving and restoring this stunning tract of land in as close to a natural state as possible.

The Serengeti covers nearly 15,000 square kilometres of magnificent Tanzanian land, and its rolling miles of short grass plains provide an exceptional landscape for wildlife viewing. This land is justifiably famous for its huge concentrations of wildlife, especially the big cats. It’s also the stomping ground of the Great Migration; a massive accumulation of 16 million wildebeest, 200,000 zebras and 350,000 gazelles, stretching their legs over 1,200 miles in an annual race to find enough water and green grass for their survival.

History of the Serengeti National Park

A sign hangs in an entrance gate to the Serengeti proclaiming, ‘This is the world as it was in the beginning’. While it is hard not to romanticise the likelihood of this claim when alone among its vast ancient boulders strewn between land and sky, this single expanse of the world has had its fair share of history.

Around two hundred years ago these wide plains, the realm of various pastoral nomad tribes, became Maasailand, or ‘Seringit’, as the Maasai called it, as the tribe swept southwards from Kenya. The Maasai lived at one with the natural order, and created their homes from the wood and mud of the land. Armed only with a spear at the best of times, they made little or no adverse impact on the environment, killing only the odd lion in a show of bravery or for self-protection.

The first organised safaris began here in the 1920s when international professional hunters became aware of the rich game pickings and forged routes in. Rumours of the large population of lions brought the area to the attention of the world, and in 1929 the central section of the present park, around the Seronera Valley, became a full game reserve.

In 1950 the Serengeti was made a closed game reserve, in which certain species were fully protected, and a year later it was established as a National Park. Until 1959, this included the Ngorongoro Highlands and crater, but these were then sectioned off as a conservation area and used to re-house any Masaai remaining within the Serengeti’s boundaries. Its perimeters were also extended to the north and south after the importance of these areas as the path of the annual migration was highlighted by the head of the Frankfurt Zoological Society, Professor Bernard Grzimek.

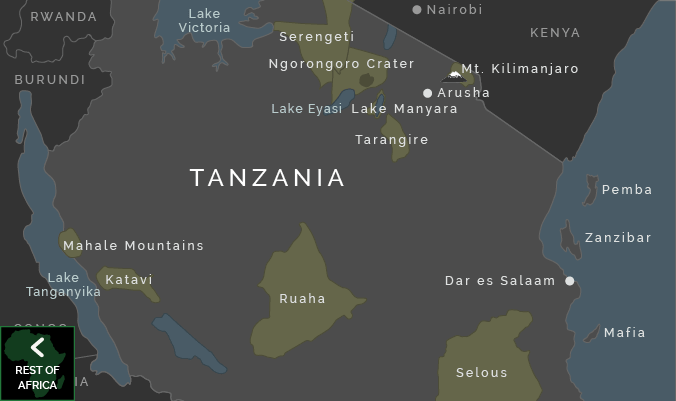

The Serengeti National Park is broadly divided into three distinct areas; the Seronera Valley and Seronera River, the Western Corridor and the Northern ‘Lobo’ area that extends northwards to join the Maasai Mara. There is always plenty of migratory wildlife action and endless photo opportunities for the snap-happy.

Seronera – Central Serengeti

The most popular entrance to the Serengeti is the southern Naabi Hill Gate, which opens onto the Seronera Valley; a vibrant wildlife area at the heart of the Serengeti. The Seronera is characterised by mainly wide open grassy plains patched together within a network of rivers that ensure year-round water supplies and keep this region incredibly rich in wildlife.

This region in particular is studded with distinctive rock kopjies (pronounced ‘copies’, from the Dutch meaning ‘little head’), sporadic collections of huge granite rocks, weathered through the ages to form distinctive softened shapes rising out of the plains; a haven of shade and water for all animals through the dry season. The kopjies also make excellent navigational features: Simba, Gol, Barafu, Maasai, Loliondo and Moro kopjies are the most prominent and best known.

There are Maasai rock paintings up to a couple of hundred years old still visible at Moro Kopjies, just about accessible through the surrounding bush during the dry season, (the path gets wildly overgrown after the rains), and only ever to be attempted after a thorough search for resident lion. The Seronera Valley has resident herds of buffalo, topi, hartebeest and impala, waterbuck, reedbuck and dikdik, numerous giraffes, warthog, and a rich pageant of birdlife of all colours and sizes.

The numerous prides of lions here are so renowned that they enticed the first safari game-hunting expeditions here a century ago, and these rolling southern plains down to the Naabi Gate are the area in Tanzania in which you are most likely to encounter cheetahs. The lines of sausage trees along the Seronera riverbanks provide the perfect environment for languid leopards to camouflage themselves on sun-dappled branches and lions roam at large throughout.

Lobo – Northern Serengeti

The landscape changes as you head north from Seronera. Beyond the Orangi River, the land opens out into wide open Togoro plains, clear and sunbaked and seemingly perfect cheetah terrain, although they are rarely spotted here.

The route continues like this for about three hours, until you reach the hills and huge worn-smooth rock kopjies of the Lobo area; the haunt of at least two extended lion prides. Further north is the Mara River, which marks the border between the Serengeti and the Maasai Mara in Kenya. Although a passable road leads across, the border crossing is closed to tourists.

This northern region of the Serengeti is bordered by the Loliondo Game Controlled Area, which extends southwards to meet the northern boundary of the Ngorongoro Conservation area. The landscape in this region is stunning and barely visited by tourists.

Those who do travel the distance are richly rewarded, whether they chose to fly in with Conservation Corporation to enjoy the finery of Kleins Camp, or whether their taste for adventure has led them on a walking and camping expedition with Hoopoe Adventure tours. Hoopoe developed a Community Conservation Project at Loliondo that was ‘Highly Commended’ by the British Guild of Travel Writers for their ‘Silver Otter’ global award for eco-tourism in the year 2000.

Here, in return for their extensive co-operational support of the Maasai village of Oloipiri, Hoopoe clients enjoy an exclusive camping concession and opportunities to meet and walk with local tribespeople.

Being just beyond the park boundaries, guests are free to enjoy night drives and walking safaris of any duration and combine their wildlife viewing with village and town visits. The village has developed clean water supplies and medical and educational facilities.

This region is distinguished by the huge coloured granite rock formations that surround the camp, and the extended views across rolling grasslands and wooded hills and water courses are fantastic.

Grumeti – The Serengeti’s Western Corridor

To the west of the Seronera, the Serengeti branches out along the westerly reaches of the Grumeti River, in an area called the Western Corridor. This area is more wooded than the Seronera, and although it still has a good population of resident game, it is harder to spot them in the bush.

It is worth taking a guide who knows the area if you’re visiting this part of the national park.

This region is particularly worth visiting in June and July, when the migration moves northwards from the Seronera and must face up to the often fatal challenge of jumping across the crocodile-infested Grumeti River. Many of these resident crocs rely entirely on this spring-time annual feast, and spend the subsequent months of the year in an idle, yellow-toothed, mud-covered wait.

A Guide to the Great Wildebeest Migration

During the months of the Great Migration, all that can be seen to each distant horizon is wildebeest after wildebeest. These are joined by herds of gazelle and zebra, who share a curious symbiotic relationship with the wildebeest, as zebras have a natural sense for the presence of danger, and seek safety in a crowd of grazers that are slower and more stupid than themselves.

You are more likely to come across bloody death scenes while the migration is around, as all predators from cats to crocs make the most of the easy pickings. A common indication of a kill is rapid hyena action, or vultures circling like dark specks of ash in a single area of the sky, then swooping to land.

The migrating herds follow a broad pattern of movement and behaviour through the months of the year, but the exact speed and location of the migration are as unpredictable as the weather. They move following the rainfall, or promise of it.

Migrating animals cannot be relied upon to be in any one place at a set time, and thus holiday plans cannot always be tailored to coincide with the hordes. But mobile camping safaris are often altered to fit the pace of that year, and driving safaris can generally find the action.

When Can You See the Great Migration?

Between January and February, the migrating herds are based across the plains on the borders of the Serengeti and Ngorongoro Conservation Area, west of Olduvai Gorge. These months are the calving season, with most zebra foals born in January, and the majority of wildebeest calves born in February.

In March, the herds spread out across the short grass plains of the Serengeti, crossing the boundaries around the Naabi Hill gate and expanding wider as offspring increase the numbers. Through April and May they remain in the southwest, slowly shifting into the central plains on the Serengeti side of Naabi Hill Gate to the west of Seronera.

In June to early July, the herds move through Seronera regions and on up into the Western Corridor. Through August they continue northwards until they reach the Maasai Mara in Kenya and remain there for September and October.

During November the herds spill back down the North Eastern strip, until they return to the plains just outside the Serengeti Naabi Hill Gate in December.

Serengeti Balloon Safaris

Serengeti Park rules and regulations are desperately strict. They have to be in order to preserve this magnificent wilderness, though it does limit opportunities for taking much energetic exercise.

Zooming around in the bush searching for wildlife action is adrenaline-inducing and tiring enough in itself, but for that real heart-stopping edge of extra excitement, the only answer is a balloon safari. These are only operated in the Seronera region by Serengeti Balloon Safaris. Find out more about how to arrange a Serengeti balloon safari here.

Balloon safaris take place in the early morning, and all the hotels and operators will ensure that you are picked up and transported to the launch pad during some dark hour before dawn. We recommend that you take a warm jumper for the occasion!

The balloon is assembled in the gathering dawn, and passengers embark into a horizontal basket that is then gently puffed vertically as the vast bubble overhead inflates. This is a fantastic way to get an entirely different perspective on the plains below, giving you a true sense of the vast spaces below and providing fabulous photographic opportunities.

A balloon trip is especially good if the migration is in the Seronera region, as otherwise the game-viewing potential is slim. The trip is followed by a sumptuous champagne breakfast in the shade of a spreading acacia with great views all around.

Breakfast is a lavish and jolly affair, spread along a long and sociable table with much merriment and warmth as the sun finds its heat. However great the lure of floating over the Serengeti in a hot air balloon, when you consider the price this is certainly a treat.

The price changes marginally with the seasons, but generally costs around $375 per person for the whole trip.