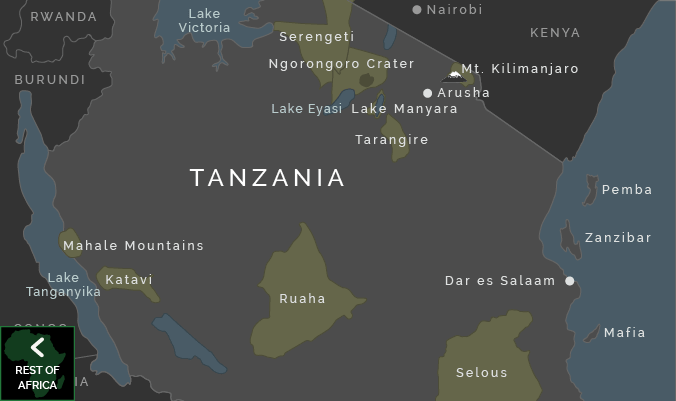

On the western edge of the Great Rift Valley, halfway between the grand expanse of Lake Victoria and the reaches of Mount Kilimanjaro, the Ngorongoro Conservation Area covers 8,300 square kilometers of the geologically bizarre landscape. It is largely made up of a range of volcanic peaks called the Crater Highlands which encompass a variety of different habitats, from Olduvai Gorge, where Professor Leakey excavated evidence of human existence that pre-dates all others, to Ngorongoro Crater, famous for its ‘microcosm of East African wildlife’.

The route into the highlands climbs steeply through a rich growth of spectral moss-draped trees, rising out of the mists that often hang around them. The land is high and green at the topmost altitude and summons a daily blanket of clouds to smother its wide expanse on most mornings. These rolling highlands sweep towards the sky, their furthest reaches revealing a richness of life that forms a hazy pattern through the distances.

The hillsides are speckled with zebra, the grass marked with dark circles of spots which are the round Maasai ‘bomas’ or family homesteads. Here and there the distinctive red of the Maasai shuka cloths might catch your eye beside a herd of tawny cattle. It is always a place of unusual beauty, especially after the long rains when the two-tone green grasses ripple in the wind and the cattle are fat.

Ngorongoro Conservation Area – History

The strange landscape of the Ngorongoro Conservation Area has a history that extends beyond the reaches of knowledge into prehistoric times. It begins over three and a half million years ago when Ngorongoro was a vast volcano, probably greater than Kilimanjaro. Its intensely violent eruptions over the years blew the top inwards and filled the cone with ash, leaving the formation standing today as the largest unbroken volcanic caldera in the world. The ash preserved an extraordinary catalog of prehistoric human life in distinct layers at nearby Olduvai Gorge, where Professor Leakey was to discover the earliest known traces of hominoid man, a sequence of perfectly preserved footprints.

The southwest boundary of the Ngorongoro Conservation Area borders Lake Eyasi, near Olduvai Gorge, in the area where the Hadzabe people live. The Hadzabe are thought to be the last remaining enclave of the most ancient Tanzanian cultures – their language is similar to the click-language used by southern African bushmen, and they continue to follow a traditional hunter-gatherer lifestyle across the savannah around Lake Eyasi. Yet it is becoming increasingly hard for these people to cling to the traditions and instincts of their ancestral traditions, as the increasing population of neighboring tribes and the extended boundaries of the National Parks have decreased their hunting grounds and depleted their water sources.

Ancient remains of cattle bones, hammered stone bowls, and tools found on the crater floor suggest that a later culture of pastoralists lived in the Serengeti and Ngorongoro Craters up to 10,000 years ago. They may have been responsible for digging wells and channels into the water courses on the highland plains and left large circles of stones on the leeward side of plains, which were probably used to pen their cattle. It is thought that the Iraqw people also settled in Ngorongoro when they discovered the area around 2,000 years ago.

Ngorongoro Historic Settlements

The Iraqw Cushitic language indicates distant origins in Ethiopia, and their lifestyle originally combined pastoralism and cultivation. Their traditional use of advanced irrigation methods suggests that they may have originally been responsible for the unusual remains of very early irrigation at Engakura. The Iraqw have since moved up onto the high Rift Valley plateau to farm the fertile reaches between Lake Manyara and the Ngorongoro Highlands, where their skill in cultivation is plainly evident over wonderfully fertile hillsides richly patterned with crops.

The Iraqw were followed into Ngorongoro in around 1700 by the Datoga people, including the most warrior-like group known as the Barbaig, all Nilo-Hamitic speaking pastoralists with similar traditional structures to their successors, the Maasai, who arrived in Ngorongoro in the early 1800s. At this time the Maasai were organised almost exclusively but war, and their fierceness was well known to the 19th-century explorers and caravan trains who were frequently thwarted by the hostile Maasai tribes in the southern reaches of Kenya and Northern Tanzania. The Barbaig had taken control of the craters and Highlands by the sheer force of their warrior class, but when the Maasai invaded them in turn, the battle between the two tribes was closely matched and hard fought.

Although the Maasai emerged as the victors and forced their fellow cattle herders back into the regions around Lake Eyasi and the mountains west of Tarangire, both tribes remember the wars here with reverence and respect. The Maasai refer to the Barbaig as ‘Mang’ati’, meaning ‘respected enemy’, and Barbaig elders still make pilgrimages to honor the graves of their ancestors in the Lerai forest on the crater floor.

The first Europeans settled in the crater a century ago under the rule of Deutsch Ost-Afrika, at the time of German colonisation. Some settled on the cool highland slopes, but two brothers divided the crater floor between them and each built a farm, cultivated crops, and attempted to keep a herd of cows, despite the Maasai continually reclaiming them. Legend tells how the brothers were so distraught at losing their cattle to warriors and lions that they turned to a colonial hunter, appropriately blessed with the surname Hunter, and paid him to rid their crater home of pesky predators.

Hunter did a masterful job of depleting the lion’s pride, so much so that when one of the brothers died in unfortunate circumstances, the other offered Hunter his brother’s half of the crater for a guinea. Hunter was taken by the offer but was soon called away to Mombassa, and never returned. The remains of both farms can still be seen—one is a set of ruins to the north of the Munge stream, and a part of the other is now used as the Ranger post beneath the wildlife lodge.

The NCA was the base for the research carried out by Professor Bernard Grzimek and his son Michael that highlighted the need for immediate action to preserve the wildlife here. Michael died in an airplane crash in this area, and he and the work he did to safeguard this place of natural beauty are remembered on a memorial plaque on the Ngorongoro Crater rim, inscribed with the words, ‘It is better to light a candle than to curse the darkness.’

Today the Ngorongoro Conservation Area Authority manages the Crater and a vast swathe of the surrounding highlands. This is a fascinating model for native communities and conservation projects and an important experiment in multiple land use. It aims to strike a balance between protecting wildlife, safeguarding the interests of the resident Maasai tribe, and providing for the needs of tourists, in order to create an environment in which all can enjoy as natural an experience as possible.

Ngorongoro Conservation Area – The Maasai

Of the 129 recognised tribes in Tanzania, the distinctive features and reputation of the Maasai tribe are perhaps the most familiar to tourists, especially those visiting the Northern Parks and the Ngorongoro Conservation Area and surrounding regions such as the Maasai Steppe. The Maasai people have lived and grazed their cattle on this land and the present Serengeti, Tarangire and Lake Manyara National Parks for over 200 years.

Now they continue to uphold the principles of their tribal lifestyle and dress in the face of the modern world, although it impinges ever more on their pastureland and on the traditional beliefs and practices that are the essence of their existence, and increasingly restricts their freedom on the land. With the combined force of the colonial and post-independence governments, they have become considerably more peaceable over the last century, and no longer inspire the overwhelming terror, raiding for cattle and wives, of which their ancestors were once so proud.

The Massai’s History and Culture

The Maasai are pastoral nomads, thought to have emigrated to north Tanzania by following the course of the Nile southwards from southern Sudan. History tells that the tribe originally aimed for South Africa, but was thwarted by sickness and combat with the WaHehe at Dodoma. Now the most southern Maasai families are settled across northern Tanzania and extend back north into Kenya’s Maasai Mara. Their nomadic path has been curtailed, and their original dream realised in a very different land.

The tribe is organised into a rigid age and class system that intends all boys to become warriors and developed a fearsome reputation as they pressed forward. Traditionally they survive on a strict diet of just the blood, milk, and meat of their cattle and increase their numbers by encouraging polygamous marriages. They came into endless conflicts with neighbouring tribes, who they attacked to steal their women and cattle: the most problematic traditional belief held by the Maasai is that which tells, ‘First God created the Maasai, after which he created cattle to keep him alive, thereby making all the cattle of the world his by Divine Right.’

Their skills at rustling have caused generations of strife with their neighbours, and most of their neighbouring tribes in Tanzania, including the Datoga, Hadzabe, Chagga, Pare, Shambaa, and Sandawe, have at some time in their history come into conflict with the Maasai. Many of these resorted to extreme measures such as digging caves and building fortresses to protect themselves, although these days the heavy hand of colonial and Tanzanian law has effectively curbed the Maasai’s more antisocial practices and a certain degree of peace has evolved between these neighbours.

The Maasai remain very distinctive but have had to make concessions. The preservation of their livelihood is a topical issue, especially since they have been moved out of National Parks such as the Serengeti, Lake Manyara, Tarangire, and Arusha. The Ngorongoro Conservation Area has made special allowances for their cyclical nomadic lifestyle to which the fertile grazing pasture and permanent water at the Ngorongoro crater floor are crucial.

These same regions are most attractive to wildlife, and only the Maasai may bring cattle here to graze. The Maasai have been allowed to remain in the Conservation Area because their lifestyle has traditionally been compatible with the wildlife and the land. They would never kill a wild animal for food, adhering to their cattle-based diet. A Maasai who kills a lion, however, is feted for his bravery and will be given cattle and even wives. The Maasai claim that the Ngorongoro lions are afraid of them, and the traditional songs that boys sing to girls during dancing ceremonies include such boasts as ‘I am strong/I killed a lion/I stole a cow/and ate it all!’

The Maasai tribe, though allowed to live in most regions of the Ngorongoro Highlands, may not settle inside the Ngorongoro Crater, though they may venture there on foot to graze and water their cattle. The very cold highlands of the Ngorongoro are not entirely suited to the Maasai clothing and life, but there is water and pasture all year round, and the population has increased dramatically from around eight families during the 1970s to a number of extended villages and family ‘bomas’ today housing hundreds of people. Their distinctive red cloth, called shuka, is rubbed with natural dye to create its striking colour, and with fat to make it waterproof and warm, helping the Ngorongoro Maasai to withstand severe changes in temperature.

Ngorongoro Conservation Area – Traditional Tribal Structures

Maasai tribal life is strictly structured into age groups. Each is assigned responsibilities designed to ensure the well-being of the tribe, reflecting traditional concerns such as inter-tribe rivalry and increasing the cattle herd. All boys are expected to spend their early years looking after the cattle in open pastures. Between the ages of 7 and 16, they move gradually further afield in the search for water, often accompanied by warriors from the next age group who protect the band from other tribes and natural dangers and teach the younger boys the ways of war and bush survival. The early years are the time to practice with slingshots, spears, and arrows, and to learn from the elders who occasionally accompany the group to teach them about natural medicines and tell stories. Boys must be circumcised before they become warriors; this is carried out as a major ceremony every seven years or so to include all boys in the age group, usually aged between 11 and 17.

Boys preparing for their cleansing ceremony that follows circumcision are called Sikoliyo. They are sent into the bush, usually for around three months before the ceremony, during which they paint their faces with white dyes, live in wood shelters, and catch their own food. Often they decorate their heads and bodies with ostrich and guinea-fowl feathers from birds they have caught themselves. Their pre-ceremony preparations frequently include a session of eating extensive amounts of beef, blood, and milk with the help of a concoction of boiled acacia bark and other ingredients called kiloriti, which enables the digestive system to assimilate inordinate amounts of meat. This is also used at times when men need to be strong or to overcome illness; it is said that after a session of kiloriti one man is able to eat an entire cow.

It may take from three months to a year before the boys are officially proclaimed as Murran, part of the warrior class. They grow their hair longer, decorate their heads with ornaments and paint their faces with ochre, and take on a spear and the responsibilities of their new age group. Each remains a moran warrior for about 10 years until ‘middle age’ brings the ceremony that takes them from warrior to mature and respected elder with the ceremony of ‘stick and tail’. At this time each man’s mother shaves her son’s head, and for the first time, he is allowed to drink alcohol, specially prepared for the celebration from a mixture of fermented aloe roots and honey. From this time on he becomes part of the collective government of the camp, deciding issues from crime and punishment to interaction with the outside world, advising the children, and telling history and stories.

Roles of the Maasai Tribe

Maasai women, distinguished by their layers of ornate beadwork necklaces, long earrings, and headdresses, do not have such a varied or exciting life plan. They tend to marry very young and are often promised a future husband before they are old enough to have any views on their future, sometimes before they are born. Their responsibilities are then so numerous as to leave little time for any activity beyond the call of duty. Maasai women must collect all the food, feed all the children, count the cattle at night, be responsible for the well-being and milking of cows, collect firewood, build fires and cook. They even build family huts, covering a shell of sticks with cow dung and patting it smooth. Unsurprisingly, their life span is less than half that expected for western women.

The huts usually have a curving passage to get into the central chamber, where the fire is a central feature. One small hole acts as a chimney, and the house becomes a warm, dark, smoky warren, divided into two to allow young cows to live and sleep alongside the family for warmth and safety. Each family’s accommodation is arranged into a circle of huts, called the boma. The arrangement of these shows the number and order of wives in the family, with the first wife on the right hand of the man, the second on the left, the third on the other side of the first, the fourth to the left of the second, and so on. The husband tends to move in with the youngest wife and pay regular visits to the others.

The tribe has historically held polygamous marriages as the ideal, and so kept the tribe populous when the warrior class frequently suffered heavy losses and the survival rate of children was low. But the speed of their population increase in conjunction with diminishing free land has forced the Maasai to re-evaluate their traditional lifestyle. Many Maasai families are beginning to imitate other tribes, turning to cultivation, keeping fewer cows, and expanding their diet. Yet very often Maasai remain fiercely true to their cultural roots, spending many years in successful higher education, then returning to the tribe and re-adopting their cultural ways.

A number of those who have remained in society have had extremely bright and successful careers, with several rising to parliament. In particular, Prime Minister Edward Sokoine, second to Nyerere and billed to take over after him, was of Maasai origin. He suffered a fatal car accident on the road between Dar es Salaam and Morogoro at the height of his career. He is remembered in almost every Tanzanian town and city, where there is invariably a street named in his honor, and the University at Morogoro is named after him.

Ngorongoro Conservation Area – Ngorongoro Crater

The famous Ngorongoro Crater, the world’s largest intact caldera, is in an exceptional geographical position, forming a spectacular bowl of about 265 km2 with sides up to 600m deep. This is the stalking ground of around 20,000 to 30,000 wild animals at any one time, the most densely packed concentration of wildlife in Africa. The Crater floor’s environments include grassland, swamps, lerai forest (small patches of the forest made up of yellow-barked acacia or ‘yellow fever tree’), and Lake Makat, a central soda lake filled by the Munge river.

These habitats attract all kinds of wildlife to drink, wallow, graze or hide, and although the animals are free to move in and out of this contained environment, the rich volcanic soil, lush forests, and spring-fed lakes on the crater floor incline both grazers and predators to remain. The crater thus holds an astonishing microcosm of East African wildlife within its boundaries. As such, it has achieved renown as the ‘eighth wonder of the world’, and attracts a growing number of visitors: even if time is limited this natural but accessible small caldera ensures a rewarding safari. Ngorongoro Crater is one of the areas in Tanzania where you are most likely to see the endangered Black Rhino: a small population is thriving in this idyllic and protected environment—one of the very few areas where they continue to breed in the wild.

However, the popularity of the Crater is creating problems that need to be addressed, as the number of vehicles allowed to cruise its overused paths at any one time continues to increase, and visitors are finding their experience marred by crowding during peak season. It is a shame because the location has much more to offer: many tourists who come to enjoy a wildlife safari in the Crater overlook the possibilities for walking and exploring in the stunning highlands and smaller craters are also included in the conservation area.

When viewed from above the Crater looks vast, with herds of buffalo or elephants reduced to the size of ants. It is an amazing feeling to gaze down from any of the lookouts or strategically placed lodges and campsites on the crater rim and see the complex and numerous lives going on 2,400 ft below. The sensation is one of elemental elevation, a godly perspective that warps all sense of size. But a cunning reverse-Tardis effect takes place as you enter: the famous crater feels surprisingly small once inside, and one day is quite sufficient to drive around. Its size means that you are likely to encounter many other vehicles, and the strict opening hours of the descent road, 7 am–4 pm, can give the safari experience in the crater a somewhat constricted feel.

Ngorongoro Conservation Area – Around the Ngorongoro Conservation Area

Beautiful forests and a deep lake can be found at the less-visited Empakaai Crater. Although at only 6km across it is much smaller than Ngorongoro, it is worth a visit for the scenery alone. To get there is a hard slog, perhaps a 4–5 hours’ drive each way on a rough and rugged track. Accompanied by an armed ranger (to ward off potentially surprised and angry buffalo) you can take a couple of hours or half-day walk into the crater, which is densely forested and inhabited only by buffalo and the odd Masaai, although the latter tend to stay around the top. The rim offers excellent views of Oldonyo Lengai, the Great Rift Valley, and Lake Natron from the northern and eastern sides, and distant peaks of Mount Kilimanjaro on a clear day, though it can often be very misty and cloudy.

Just beyond the NCA boundaries, Oldonyo Lengai is an impressive volcanic crater cone, now the only remaining active volcano in this region. Its continuous grumblings, bubbling, and steaming earned it its Masaai name; ‘mountain of the gods’, and the strange dark peak is held in great regard in all Maasai legends and traditions. Many Maasai have climbed its slopes accompanied by a village elder to make sacrifices or prayers – women seeking to be blessed with children, boys seeking to learn the wisdom of men.

Dust and ash from its eruptions, blown northwest, created the fertile Serengeti Plains, with the help of its now dormant neighbours. It is possible for visitors to arrange to climb its steep and sulfurous sides to peer into the tumultuous crater, but many are content with a more distant view. Views of this legendary pyramid mountain are particularly good from the rim of Empakaai, and from the surrounding peaks of Makarot (also called Lemagrut), which are only accessible on a walking trip.

To the east side of Empakaai crater, just beyond the boundaries of the NCA, lies an important archaeological site, although its history is still shrouded in doubt and mystery. This is the ruined ‘city’ of Engakura, a highly advanced web of ancient stone dwellings based on a complex irrigation system. At close quarters it is hard for anyone but the most curious archaeologist to gain much from the stone rubble that remains, but aerial photographs reveal an intricate network of lines that show a distinct picture of a developed civilization.

More Areas Worth Exploring

The question remains as to who was responsible for building Engakura, which dates from around 500 years ago. Elders of the Iraqw tribe claim that they inhabited that area before ‘marauding warriors’ forced them to move on. But although the Iraqw practiced cultivation they have no history of irrigation or building in stone. Others believe that Engakura might have been the work of a Bantu people called the Sonjo who now inhabit an area further north and west of Lake Natron and have traditions of irrigation, though they do not build in stone either. Engakura is a long drive from the Ngorongoro Crater and is only worth including on an itinerary if you have a special interest in the area and are prepared to camp overnight in the northern reaches of the Conservation Area.

Another fine spot off the beaten track for walking and scenery is Olmoti Crater, west of the track between Empakaai and Ngorongoro craters, where the spring source of the Munge river breaks through a notch in the crater rim to create a fine waterfall. If you call the ranger post at Nainokanoka and negotiate to take an armed ranger with you, you can walk through the forest up to the top of the fall, although if you are with a responsible tour operator this may not be necessary.

To the western side of Ngorongoro crater is the site of Professor and Mary Leakey’s discoveries, hominoid footprints dated from around 3,600,000 years ago, which can be seen in their original form at the conservation area at Laetoli, or otherwise at the Olduvai Gorge Museum. Olduvai Gorge is named after Oldupai, the Masaai word for the wild sisal plant that grows ferociously in this area. It is said that German interpreters misinterpreted the name, and it is now commonly pronounced and spelled Olduvai. Four different hominoids were discovered in the rock strata of the river canyon, showing gradual stages of development over 2,000 years. The Olduvai museum charts the findings and gives some background information. It can be visited as a detour while travelling between Ngorongoro Crater and the Serengeti.

To the north of Olduvai Gorge is a curious black sand dune called the Shifting Sands, in reference to its steady progress across the plains. It moves about 17m a year, retaining its pure windblown form, a small black heap of volcanic ash. It is a slow and bumpy drive from Oldupai, followed by a long and slow drive back to the main road. The views are lovely, but it might mean sacrificing precious hours in the Serengeti.