Arusha

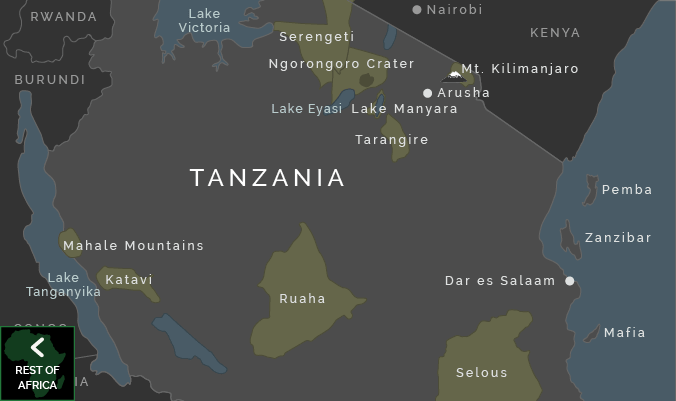

Surrounded by some of the most fascinating and varied national parks in Africa, Arusha sits snugly on the foothills of Mount Meru in a wide expanse of high and fertile volcanic land. To the northeast, the impressive silhouette of Kilimanjaro looms against the sky, while just a short distance northwest lie the plains of Maasailand, the mountains, rivers and lakes of Ngorongoro, Manyara, Tarangire and the plains of the Serengeti.

Arusha has its own National Park, tucked behind the wide coffee plantations that flank the Moshi Road, which spans a curious landscape of lakes and craters. The park includes a large portion of Mount Meru and provides a scenic and quiet haven just a few minutes’ drive from the town centre.

Skirted by rapid, haphazard growth of shanty stalls and housing, this old German garrison town in the middle of Maasailand is vibrant, colourful and thriving in its role as the northern centre for commerce and safari operations. Most international tour operators liaise with specialised operators based here for all explorations of the surrounding National Parks.

Arusha was once the centre for the East African Community, an alliance between Tanzania, Kenya and Uganda. Its Conference Centre is now the base for the War Crimes Tribunals being negotiated between Rwanda and Burundi and remains an important centre for business and commerce in northern Tanzania.

As you arrive, whether by air or by road, panoramic views of the surrounding countryside reveal a fertile and well-cultivated land lush with plantations of coffee, maize, beans, and wheat, alongside greenhouses and fields growing fresh flowers for export. This productivity is reflected in Arusha’s markets and on most street corners, where astoundingly large avocados, tomatoes and maize cobs are among the crops offered for sale.

As a result of its prosperity, Arusha is very attractive to settlers and its population has grown rapidly: from an estimated 5,300 in 1948 and 100,000 in the 1970s, the population today is probably closer to 400,000.

There is a group of people still known as the ‘WaArusha’, a term which refers to a small group of people who originated from an area known as Arusha Chini, originally thought to have been a combination of Meru and Chagga tribes. In the trammels of time, these people were conquered by the Maasai, and subsequently assimilated many aspects of Maasai dress, language and social structures, but it is said that their accents and physical appearance remain distinct to discerning locals.

Today, Arusha inhabitants are a diverse mix of nationalities and backgrounds: Asian, European and African professionals, tour operators, street traders and shanty dwellers are all arrayed in distinct urban sectors radiating from the centre of town.

The town centres around the old German boma and clocktower, close to the AICC and numerous offices of safari operators. Businessmen and loud-mouthed salesmen thread through lines of Maasai women sitting shoulder to shoulder in shop doorways, making traditional coloured bead jewellery.

Just a few metres away, the small but motley population of homeless people and beggars joins the swirling crowd, and everywhere tourists are assailed by a constant stream of requests to buy batiks or another Swahili–English dictionary. The overall atmosphere is friendly and welcoming, and Arusha offers a cosmopolitan range of restaurants, good shopping and several day trips to the singularly impressive and varied landscapes that surround the town.

The History of Arusha

The people of Arusha were established as a distinct tribe of pastoralists and farmers long before the colonial powers arrived. Influenced by their Maasai background, they kept a similar social structure, with status related to age, and a central warrior class. They were occasionally called upon to support Rindi, the great Chagga warrior chief, in his battles with other chiefs around Kilimanjaro, and when the first German settlers began involving themselves in these altercations, the Arusha were no strangers to fighting.

German Occupation

On 19 October 1896, German Captain Kurt Johannes approached the Arusha in an attempt to secure diplomatic relations with local chiefs, but the Arusha warriors, unable to forget a German raid of the previous year, attacked and killed two missionaries. Captain Johannes returned to his base in Moshi, and persuaded Rindi to side with the colonials and mobilise Chagga troops to retaliate.

The Arusha were easily defeated by the punishing onslaught: their weapons and food reserves were confiscated and their houses were destroyed. They were finally forced to bow to German control.

In 1899, the Germans began construction of a strong fortification, a boma, and the Arusha were forced to build it. Maasai in Arusha today still remember the humiliation of this task: the new colonialists had a penchant for travelling around on the backs of the Arusha and Maasai men, egging them on with whips.

One Maasai recorded in his memoirs how an unsurprising resentment at this form of transport grew; he was particularly upset to have an unusually heavy cargo. One day, passing the river with his charge set heavily across his back, his patience snapped and he tossed his ‘master’ into the water.

The Maasai realised that the consequences would be severe, and a large number of them ran away into the bush. After a couple of days, a Maasai chief was sent to find the mutinous group. He explained that he was acting as a mediator and that if the group would return to work all would be forgiven.

The runaways marched back into the new Arusha town in a column of about 400 men, and as they strode down Boma Road, the entire troop was gunned down in the street. It is said that the mediator was promptly promoted.

The fort was completed in 1900 and became a barracks for 150 Nubian soldiers. Later it became the regional Government office until 1934, when it became the Arusha Museum of Natural History.

Trade History

A steady influx of traders and farmers into Arusha, notably Indian traders, private German farmers and immigrant Africans, created economic growth in Arusha. Meanwhile, the German administration had conceived an idealistic vision of a vast white settlement of their own construction and attempted several schemes to import large numbers of settlers from bizarre backgrounds.

The first of these plans backfired when the Boer farmers of German origin who had taken up the offers of farmland proved too uncouth for the ideal community; they were mainly squeezed out into Kenya. The grand scheme was revised: now they would import 10,000 German peasants from settlements around the Volga Basin and the Caucasus in Southern Russia.

The four families who arrived as a test project were painfully disappointed to discover that Arusha did not have four harvests, as they had been led to believe, and soon made their way to Tanga, begging to be sent back to Russia.

The first school was constructed in 1914, called Boma School. It is now the site of Arusha Lutheran Church. The railway to Moshi was completed in the 1920s, and this boosted Arusha’s position at the centre of trade and development in Northern Tanzania, at the heart of the coffee-growing regions.

Presidential Position

The population of Arusha continued to grow, and eventually the town earned enough status to earn its place in history as the site of the first president, Julius Nyerere’s, most influential political dictates. His 1967 Arusha Declaration delineated his most influential policies for a ‘Model of African Socialism’, a confluence of rules and ideals that would influence the livelihood and outlook of the nation for the next 20 years.

Mount Meru

One of the major attractions of Arusha National Park is the crater of Mount Meru, Africa’s fifth-highest peak. The rugged ash cone of this dormant volcano has not seen any lava action for a century, and is not predicted to do so soon, so those wishing to climb its 4,566m height can eliminate at least one concern.

A hike up and down Mount Meru is usually a three or four-day round trip, if you take it at a relaxed pace and explore the plains, forests, moorlands and volcanic lava desert that make up its landscape. If time, funds and stamina permit, it is a good idea to climb Meru as a means of acclimatising before attempting the summit of Kilimanjaro.

Mount Meru also has the advantage of being far less visited than its grand neighbour, so the lower slopes are more densely populated with wildlife and there is a good chance of encountering larger animals such as giraffes and various antelope.

Although smaller than Kilimanjaro, with no snow-covered peaks, the climb up Meru can be extremely cold and requires packing proper mountain gear for overnight camping. Mount Meru is also very steep in parts, and climbers will need stout walking shoes.

Many of the tour operators based in this area can arrange for you to climb Meru, and will ensure that you have appropriate porters, food and equipment. A fully equipped climb generally costs upwards of $200 per day, including the park requirements for an armed ranger ($20/day), hut fees ($20), park fees ($25), and overall rescue insurance ($20), plus the cost of a guide, porters, food and transport to the park. The price is considerably lower if you climb in a larger group. Factor in tips at around $10 per day for your guide.

Climbing Mount Meru

Most trips up Mount Meru follow an itinerary similar to the following:

Hikes generally begin and end at Momela Gate. A path leads up from here to dense mountain rainforest where huge moss-covered cedar trees grow, and there is always a chance of encounters with buffalo, giraffes and colobus.

Many climbers stop for a picnic along the way, perhaps at Mayo Falls (1,900m), to rest and breathe the fresh forest air and maybe bathe in the cold, clear mountain stream. The walk continues in the afternoon through the beautiful upper rainforest to Meru Crater and then Miriakamba Hut at 2,700m for supper and the first night on the mountain.

After breakfast, hikers traverse the lower alpine regions on the northern crater rim to reach the Saddle Hut at 3,500m. This walk is quite steep and requires a major effort from all climbers.

Close to the Saddle Hut, the vegetation is reduced to only low moss-covered bushes and shrubs that can survive such high altitudes. You will usually reach the hut by mid-afternoon and can rest or summon more energy to explore the rocky summit of ‘small Meru’, from where the views are superb in all directions, and the sharp Crater Rim leading to the Meru Summit is revealed.

You spend the night at Saddle Hut, with breathtaking views of the night sky, often above the cloud line. Climbers can start the ascent to the summit in the early morning, as early as 2am, aiming to reach the summit at sunrise. It’s best to do this climb at full moon, but take torches in case it is not bright enough.

Between the Saddle Hut and the summit, the reduced oxygen of high altitudes cuts climbers’ breath short and the pace is slow. When you reach the summit you can enjoy the first morning light while recovering from the night’s exertions.

The views are spectacular, as the orange-red sky fades behind Kilimanjaro and the morning sun rises across the African plains. The descent continues back along the Crater Rim to the Saddle Hut for a picnic stop, and on in the afternoon to reach Miriakamba Hut, for the final night.

The next day brings climbers back down to Momella Gate along a trail that winds through open glades where buffalo and bushbuck can be observed in the morning light. There are often fabulous views of the Momela Lakes and Kilimanjaro.

Shorter walks on Mount Meru

For those less energetic or adventurous, or just pushed for time, there is an hour-long walk from the open plain of Kitoto through the forest to Jekukumia River and a short distance up the mountain to either Meru Crater or Njeku. The forest ends abruptly on the rim of Meru Crater, with views of the sheer cliff face rising 1500m to the ash cone summit.

The walk to Njeku is longer and leads to an ancient sacrificial site once used by the people of Meru in times of drought. ‘Njeku’ literally means an old woman who commands great respect, but in its context here it refers to the site of an old juniper tree, which is connected to a spiritual legend about an old woman who had the power to make rain.

Continuing further on from Njeku brings you to a viewpoint overlooking a waterfall gushing through a gorge of the Ngare River.

All walks through the park must be arranged with park officials at the gate, and you must take an armed ranger for protection in case of encounters with irritable buffalo.

Shopping in Arusha

Arusha is an excellent town for shopping for art and curiosities from all over Tanzania. As the central town of the Maasai villages, it’s also the best place to shop for traditional Maasai beadwork and jewellery. Buy directly from the Maasai women sitting along the pavement, or from numerous souvenir shops around the town centre.

Souvenirs

Robin’s Nest and The Deco Shop on Haile Selassie Road both stock a great range of gifts and furniture. Craft shops between India Road and the clock tower stock a wide range of Makonde carvings, either imported from the Makonde Plateau in the south or more frequently made by ambitious Makonde carvers who have moved northwards.

Fashion

Styles have evolved to match Western demands, so look out for some interesting new pieces as well as traditional abstract and figurative styles. The most varied selection of all of these, in all shapes and sizes, is at the Cultural Heritage Centre a few kilometres west of the town centre, opposite Mserani Snake Park on Dodoma Road. Their stock is slightly more expensive but the variety and quality make it worth a visit, and they take credit cards.

Batiks are also commonly offered in the streets, but you can usually get a better price from the curio shops, where you will also find a range of souvenirs made from semi-precious stones, such as malachite, tanzanite and green tourmaline and rhodolite. Amethysts and garnets are also found in these shops, but not necessarily from the Arusha region.

Food

The four main supermarkets are Kibo and Modern on Sokoine Road, Kijenge on Moshi Road and Makwani on Swahili Street. The local markets are Soko Kuu at the crossroads of Market Street and Azimio Street, and the new Kilombero on Sokoine Road.

Books

For books, try Kase on Boma Road, which has a good selection of local ethnic and educational literature on its well-stocked shelves. New books tend to be expensive throughout Tanzania, but the range and choice, especially of non-fiction, are definitely the best here. Almost directly opposite the bookshop on the other side of the road is a second-hand stall with a good selection of well-thumbed novels.

Cultural Tourism in Arusha

An excellent new incentive executed with advice from SNV, the Netherlands Development Organization, has been developed in Arusha. It aims to give tourists a chance to look a little deeper into the country and culture that they are visiting and bring the tourist dollar within reach of local people.

These local projects remain mainly low-key, although each has developed at its own pace and all are different. The programmes introduce interested tourists to local people who have been trained as guides, interpreters and sources of information about their area.

The programmes aim to fund major local requirements, such as irrigation, education or ecological work, and tourists pay a prearranged fee for these funds. The arrangement gives people the chance to meet, to explore cultural differences and interests, and the tourist experience is often immeasurably enhanced by local introductions and explanations.

Cultural Tourism Programmes near Arusha include those at Mkuru, Longido and Mto wa Mbu. Mkuru and Longido are projects organised with local Maasai tribes, and each requires at least a couple of hours’ driving from the town centre.

The Maasai guides at Mkuru and Longido are experienced at leading and organising camel safaris, but their English is limited – although they are proficient in hand signals – so if you plan to stay for any length of time it is advisable to take a translator with you. Most tour operators will be happy to provide a guide to accompany you and arrange all the camping equipment and food that you might need.

Before visiting either of these villages ensure that you are adequately prepared, with enough drinking water (three litres a day is recommended if walking in the sun) and food, sun protection, a hat, good walking shoes and thorn-resistant clothes.

Mkuru

Mkuru is north of Mount Meru, not far beyond the Momela Gate of Arusha National Park. The people are Maasai, but this community shows its individuality in the development of a camel camp, assisted by Heifer Project International.

Camels are ideally suited to survival on the semi-arid plains between Mount Kilimanjaro and Lake Natron, and there are now about 100 of these long-legged dehydration-resilient beasts in Mkuru. You can arrange a camel-riding safari guided by Maasai warriors, either for just a couple of hours or several days, travelling to Lake Natron or Ol Doinyo Lengai.

Any trek through this landscape will encounter plenty of wildlife and birds along the way, and the views of Kilimanjaro, Meru and the Longido Mountains provide a stunning backdrop. The Mkuru Maasai will also take you on bird walks, or a rather more strenuous climb up the pyramid cone of Ol Doinyo Landaree. This last takes about two hours and from the top, there are superb views of Mount Meru and Kilimanjaro and the plains between the two.

There are three ‘luxury’ cottages at the camel camp, each with beds for two. There is a tap inside each, but the toilet is outdoors (and has an excellent view of Kilimanjaro).

No food or drink is available at the camp, other than tea or coffee with camel milk, and tour operators (or well-prepared individuals) are encouraged to use the kitchen with its energy-saving stoves to prepare food brought in on their own initiative. The project at Mkuru aims to build and run a kindergarten in the village, and will greatly improve local education.

Longido

Longido, 100km north of Arusha on the Nairobi, has an interesting local project in a rural area that still bears signs of its unusual colonial history.

Heavy fighting broke out in this region between the Germans and the British during the First World War. The local stories tell how a single German soldier hid behind a rock, sniping at the English soldiers, until a Maasai warrior was bribed to creep up behind the attacker and spear him.

The remains of an ancient graveyard, now mainly sunk into the depths of the bush, once proudly commemorated the German and British who died there. A nearby tree covered with ‘European drawings’ is not as exciting as it sounds: it has been crudely graffitied with the odd initial and some discernible dates, but the walk leads past bush huts used by boys awaiting their cleansing ceremonies and through a changing and dramatic landscape.

The number of walks around Longido merits a full-day trip, but the village can also be visited as a half-day or two-day tour. The cattle market takes place on Wednesdays, attracting colourfully arrayed Maasai from every direction of the landscape.

One of the most fascinating people to look out for in Longido is the coordinator of the tourism programme Mzee Mollel; a local Maasai who studied sociology in Zambia and Australia. He is a font of information, and a delight to engage in conversation.

Longido provides a fascinating landscape to explore with the insight and knowledge of a local Maasai guide alongside. Unusual wildlife not commonly seen in the National Parks, such as gerenuk, lesser kudu and klipspringer antelopes, are common in the bush and mountains around Longido, as are other animals such as giraffe, zebra and gazelles.

Your guide can point out birds, such as masked weavers, barbets and secretary birds, demonstrate the food and medicines the Maasai traditionally take from the bush, and take you to a boma to experience their tribal way of life and eat food prepared by the women’s group. Proceeds from the project are being put towards a new cattle dip to protect the herds against the numerous ailments that kill around 1,000 of their cows each year.

Mto wa Mbu

At the town of Mto wa Mbu, on the road into Lake Manyara National Park, the local population is made up of an extraordinary spectrum of Tanzanian tribes. This unusual group has been attracted by the fertility of the land here, transformed from an arid and unattractive land for habitation by an extensive irrigation system implemented in the 1950s.

As news of this ‘new’ land spread, people came from all areas and settled here to farm and work the land according to their own experience. Fruits and vegetable seeds have been brought from all over the country, and people of different tribal backgrounds produce food according to their traditional methods.

A visit to the tourism project at Mto wa Mbu can introduce you to local Chagga farmers who brew their own banana beer, and a farmer from Kigoma, Mzee Filipo, who makes palm oil from palm trees. Alternatively, you might head to a waterfall 5km north of town, and see the papyrus lake where local Rangi people collect papyrus for mats and baskets, and the Sandawe families make their bows and arrows for hunting.

There are several places to buy provisions in Mto wa Mbu, and a couple of basic guest houses for accommodation.

Lake Manyara National Park

Manyara is a small but scenic national park in Tanzania. It’s a good soft introduction to the safari experience; a pretty park through which a mainly forested driving route wends its way between the banks of the soda-water Lake Manyara and the impressive rise of the Great Rift escarpment.

Manyara is often visited for half a day at the start or end of a safari, as it lies en route to Ngorongoro and the Serengeti.

On reaching the National Park, you first encounter a small museum, or rather a room packed with an ageing and dusty collection of badly stuffed birds and animals. It is probably a better idea to continue into the park and take a chance with whatever might come your way in its full-bodied and living form.

Wildlife

Manyara is excellent for birdwatching, a good area to find elephants, and also offers the chance to spot a legendary Lake Manyara tree-climbing lion. The park is often awash with butterflies, particularly just after the long rains, at the end of May and through June.

Elephants, giraffes, buffalo and wildebeest can be found grazing in unexpected clearings or heading towards the water to drink or wash, and the rivers and river beds provide scenic vistas for animal spotting. Warthogs seem to thrive here, and it is a natural playground for baboons and monkeys.

The legendary tree-climbing lion of Lake Manyara, although notoriously rarely seen, has inspired extensive theorising about the wonders of evolution. It has been suggested that they may have developed their scrambling skill to escape the tsetse flies that bite below, or to get a better view of prey amid the denser thicket.

Lions have also reportedly been seen up trees in Tarangire Park and the Serengeti, although these are even more rarely spotted than those in Lake Manyara, where the low branches of the numerous spreading acacia provide a fine frame for apprentice climbers.

Tarangire National Park

To the south of the large open grass plains of southern Maasailand, Tarangire National Park covers 2,600sq km of grassland and floodplains and a large area of tall acacia woodland. It is beautifully unspoilt, and the wide views of distant, variously purpled formations of volcanic mountain ranges along the drive are superb.

Tarangire also has regions of quite dense bush, with high grasses and huge old baobab trees instead of the green forests of Manyara. The land is hilly and dominated by the impressive valley of the Tarangire River, which attracts numbers of migrant animals during the dry months, especially between July and September, when the concentration of animals around the Tarangire river is almost as diverse and as reliable as in the Ngorongoro crater.

Wildlife

The ecosystem is balanced by a localised migration pattern followed by most animals other than lions, who don’t tend to abandon their territory. The animals mostly disperse during April and May, when widespread greenery and standing water encourage all the grazers further afield. In June, the eland and oryxes begin to return, followed by elephants towards the end of the month.

Tarangire has quite a reputation for elephant ‘pow-wows’ when different herds congregate in one area around the end of the rainy season, and the dominant males take advantage of the situation to sow seeds for future generations. The following 22-month gestation period is timed so that the birth coincides with the rainy season two years later.

Zebra and wildebeest return through July, and by mid-August all the animals are congregating around their last reliable water source, the Tarangire River. The calving season falls in the early months of the year, through January, February and March, and so makes the most of the fresh grass during the rainy season.

But there are always a fantastic number of colourful birds swooping and strutting along the rough paths in front of your vehicle in Tarangire, with likely spots including the Paradise Whyder and endearing Yellow-collared lovebirds.

There are a few resident lions, easier to find when the migration arrives to excite their taste buds. In other months, they look quite mean and lean and slip easily between the grasses.

The park has become a wildlife conservation area because of its resident tsetse fly population. They are a pest, with an irritating stinging bite, but tend to hang out in swarms, and a well-planned ‘windows up’ approach seems to be the way to survive. They do not seem prevalent around any of the lodges.

Tribes of the Babati Region

Meriting the long, hard journey to get there, the Babati region is a place of great natural beauty and interest on the edge of the national park, much of which is provided by its unusual combination of resident peoples. Three main distinct tribal groups live on these hills and plains in the shadow of MountHanang, most of whom settled here following unfortunate conflicts with the Maasai tribe elsewhere.

This is the land of the Barbaig, Nilo-Hamitic-speaking pastoralists with similar social structures to their successors, the Maasai, historically reputed for their power as rainmakers. It is also home to the Tatoga people, who are renowned for their skill in developing terraces and agriculture.

The area also extends into the greater territories of the Iraqw tribe, who are thought to have originated from the Arabian Gulf region. They are also said to have migrated down the Nile and on into the Ngorongoro regions, from where some were forced further west to settle here.

It is thought that the Hadzabe people, now largely settled around the LakeEyasi region, and Sandawe bushmen ranged freely around this region before the advent of the Bantu tribes 2,000 years ago. Nowadays they tend to stay further north, but these descendants of early San-Bushmanoid groups are the most likely people to have created the unusually varied collection of rock paintings around Kolo.

The Kolo Rock Paintings

An extremely rare collection of rock paintings near Kondoa, known as the Kolo Rock Paintings, remains another mystery of Tanzania’s history, with no real verification of the date of their conception or the identity of their originators.

It seems likely that the images were originally the work of the hunter-gatherer Bushmanoid tribes, who have an ancestral history of rock art, and some Sandawe clans claim that their ancestors were responsible for the paintings. But as the collection varies so greatly in age and style, it might be that later Bantu-speaking people added their own handiwork to the older images.

It is estimated that many of them are between 200 and 4,000 years old. The research carried out by Mary Leakey in the 1960s identified nine different styles that may relate to different eras and artists.

Some of the work is black and white and some in varying orange- and brown-tinted ochres, and many of the older images have faded and suffered over time, while others have been painted over by successive generations. Many of the images could have inspired Lowry in his famous stickman paintings thousands of years later; while some are simple images, others depict oddly moving scenes, such as a group of two masked men abducting a female, while two other men try to hold her back.

Others show local animals, such as giraffes and hunting scenes with antelope racing away. There are also images of people playing musical instruments and those that seem to anticipate some kind of abstract expressionism.

Some of the paintings are quite easily accessible, following a quarter-mile walk across fields, and some are a bit harder to get to, requiring a rocky climb. Typically the most interesting and worthwhile paintings in the series are the most difficult to reach, but at least these are slightly better protected from the recent vandalism and graffiti and the weathering that has been the sad fate of many of them.

There is a very helpful guide working for the Antiquities Department in Kolo who can lead you to each of the sites, but apart from his invaluable presence, little is being done to preserve this ancient artwork. The paintings are described in detail and painstakingly recreated in Vanishing African Art which contains the research materials carried out by Mary Leakey.